- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- Joint Health / Pain »

- Put a Lid on Kneecap Pain

Put a Lid on Kneecap Pain

For such a small bone, the patella (kneecap) seems to cause a lot of problems.

Pain under the patella (or around it) carries many names: patellofemoral pain syndrome, retropatellar pain syndrome, runner’s knee, jumper’s knee, chondromalacia patella among others.

It also carries frustration for both clinicians and patients.

For decades, patella pain has been explained and treated by Structuralism – a school of thought that believes the cause of musculoskeletal complaints is from one or more biomechanical abnormalities. For patella pain, the biomechanical abnormalities include a laterally tracking patella, weak medial quadriceps, tight hamstrings, tight iliotibial band, tight calf muscles, weak or tight hip rotator muscles and overpronation of the foot. A Structuralist view would then be to set the mechanics “right” and symptoms would subside.

But, there’s a problem with this view. No one has perfect biomechanics. Most people do not train muscles, work on flexibility, for example, enough to alter or maintain biomechanical homeostasis and they don’t know their biometrics (strength, flexibility, motion, power, balance, etc.) well enough or at all to direct their training toward any specific deficit. So, most people go through life with a variety of “abnormalities” and are just fine until one day (or over a series of days) something happens and suddenly pain appears under the kneecap.

The fact is that there is a low correlation between “abnormal” position and movement of the kneecap with knee pain. In one study, 50 people who had kneecap pain were compared with 47 people who had never had kneecap pain. The painful group had better kneecap position and motion than the non-painful group as revealed on dynamic MRI.

Why Pain Appears Under the Knee Cap

The reason a person hurts under the kneecap is because the force applied to tissue(s) is greater than what the tissue can withstand. There are two primary sources of retro-patellar pain from tissue over load: sub-chondral bone and synoivum. I’ll cover sub-chondral bone today (there are sources of pain outside the knee that can create knee pain but that’s another day).

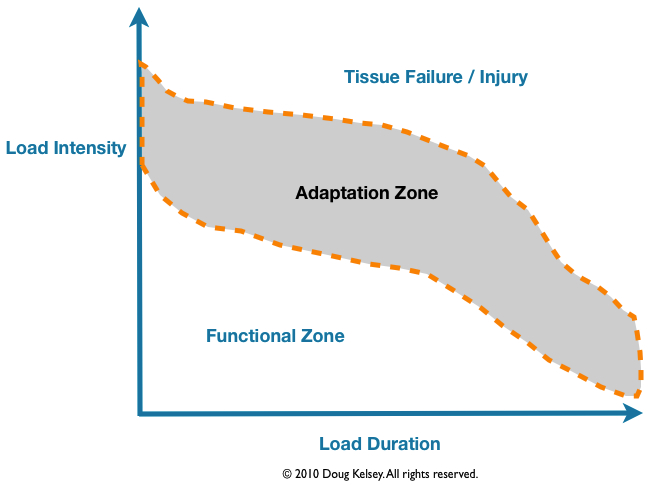

The over load can occur from a high force, blunt trauma such as a fall on the knee or a lower load, sustained force such as sitting in a three hour movie with your knees bent to ninety degrees. Physical function spans a certain range of loads or a “functional zone”. When you move outside this zone, your body has to adapt to the loads to reach a new equilibrium. If the activity or load is to far into the adaptation region, too much, too fast, too long, you then end up in the land of injury.

The cartilage under the patella serves as a force attenuator. It slows the transmission of loads into the underlying bone much like the bumper on your car protects the frame from collision. When the cartilage is too soft, the force travels into the bone at a higher rate. Whether the overload is from blunt trauma of a fall or the sustained overload of a movie, the bone under the kneecap cartilage may experience a force greater than its ability to manage it and the result is you hurt (cartilage has no nerve endings so it can’t be a pain generator). In fact, there’s actually an increase in metabolic activity in the bone similar to a stress fracture with resultant swelling.

The increase in pressure activates pain nerve fibers.

When you get up from the movie, for example, your knee may hurt for a period of time then go away. So, from a Structuralist perspective, does that mean your biomechanics improved? No. It means that your tissues were able to return to a state of biochemical equilibrium. The time for this to occur varies depending on how “fit” your tissues are, how far over the adaptation zone you were pushed and what you chose to do following the movie (move around or walk next door and sit through a meal with your knees bent to ninety degrees again).

I’m not suggesting though that biomechanics are not important to address. Weakness of the hip external rotators. for example, allows the femur to rotate inward and create focal loading points under the kneecap. But, failure to also address the tissues at risk (in this case both cartilage and bone under the patella) often results in a short term resolution of pain with long term recidivism.

Having once been a Structuralist, I understand its allure. You can sometimes see the biomechanical deviations, feel them, test them and the urge to direct all of your attention to the mechanical variants is exceptionally strong. Sometimes, it works. Most of the time, it doesn’t.

A Few Ideas

The Old School Quad Set

This exercise, often issued to “strengthen” the quadriceps, which it never does, can be very helpful for kneecap pain but sometimes you have to “tweak” it a little bit.

The idea is to tighten the muscles on the top of your thigh – the quadriceps – as tightly as you can and hold the contraction for ten seconds.

The “tweaks” are to place a small towel roll under your knee to prevent the knee from hyperextending. Many people have knee joints that extend more than normal and if so, when you tighten the quadriceps, the patella will run right into the femur which tends to hurt. The other tweak is to tighten the other quadriceps at the same time you tighten the quadriceps on the painful leg. This takes advantage of something called “hyper-irradiation” where contracting other muscles helps the target muscle(s) increase their tension.

Quad sets help your knee by improving the quality of synovial fluid in the knee which is one of the main sources of nutrients for your cartilage.

You can’t do too many quad sets. I usually suggest 100-200 repetitions per day.

Gentle Stationary Cycling

The emphasis here is on the word “gentle”. It’s very easy to push the load in your knee, while cycling, to above body weight force. Choose a light resistance – you need some to get the full benefit of the exercise – and pedal with an easy motion. Your knee should feel comfortable. At first, it may feel stiff but after a couple of minutes, the movement typically becomes more fluid. Twenty to thirty minutes per day minimum is a good place to start.

Fix Your Diet

Many people fail to consider how important nutrition is for healing and for reducing and eliminating low level inflammatory response in your body. The simplest way for me to explain what to do is this: eat whole foods. In particular, eliminate sugar and flour. White flour converts to sugar before you swallow it. And chronically elevated blood sugar increases something called “advanced glycation end-products”, or AGEs. AGE is a protein bound to a glucose molecule that then damages cross-linked proteins. As your body then works to breakdown the AGEs, immune cells secrete inflammatory messengers called cytokines.

The result is a low level of inflammation that, over time, degrades your cartilage. Fixing your diet can only help you.

The good news is that there are things you can do to reduce or eliminate kneecap pain. It’s not a quick fix however. Cartilage changes slowly. You have to keep working on it even when it seems as if you’re making little to no progress.

And sometimes, you need a coach. Joint pain can be frustrating to deal with because, at some point, you have to increase the load, change the exercises in order for the cartilage to respond optimally. If you’re not sure what to do and when, you can end up just doing exercises that no longer help you.