UPDATED: December 2019

“The way you see the problem, is the problem.” – Stephen Covey

Knee pain is a problem but it’s not THE problem. Not technically. Knee pain is a symptom but it’s a symptom that interferes with a lot of things in a person’s life so it sure feels like a pretty big problem.

When I was in PT school, I skipped most of the orthopedics lectures. Probably not the greatest thing to do but my attitude was that the lecturer, an orthopedic surgeon, was simply restating what was already in our textbook. I needed to work to get through school so I had better things to do with my time than being bored to just this side of madness several days a week.

I managed a “B” in the class but really knew nothing about how joints healed. We were taught, and this is still the case in many schools today, that cartilage had no capacity to heal. In fact, one of my professors said that you get one batch of cartilage and when you lose it, too bad.

That’s it.

So, if you had injured the joint cartilage or were dealing with osteoarthritis, well, too bad. The best you could do was to try to strengthen the muscles around the joint and hope that by doing so, your joint would be better protected.

I remember sitting in class wondering why; why wouldn’t cartilage heal? So I asked. My professor just looked at me like I was a complete idiot. Finally, he said, “There’s no blood supply and no metabolism. Tissue cannot heal without metabolism. Cartilage is biologically inert.”

Inert means “lifeless”. A chair is inert. A frying pan is inert. But cartilage? How could that be?

How could a biologic tissue be inert? It just didn’t make any sense.

So, I had to ask. “If cartilage is biologically inert, how does it live in the body?”

Silence. For a while. “It’s not biologically active. Now, let’s move on.”

I actually paid for that education too.

The Truth About Cartilage

I learned many years later that I was correct and my professor was wrong. Cartilage is not biologically inert.[source] Its metabolism though is very slow, sluggish. It has no blood supply, no nerve supply, and no lymph supply which makes healing difficult but not impossible.

I gave a lecture in May 2011 at the American Association of Orthopaedic Medicine conference on Regenerative Medicine in Las Vegas. My topic was the “Mechanobiology of Exercise” or said another way, the study of how mechanical forces generated within or imposed upon living tissues affect physiology and structure of that tissue.

I was speaking to a variety of professionals – physicians, chiropractors, osteopaths, podiatrists, scientists – about 200 people or so.

After I finished the talk, a number of people came up to me and said that they had never heard of most of the material I presented and were excited to learn that exercise had such potential to help injured tissues heal. While I had created many of the treatment techniques, much of the underlying science dates back a number of years.

We know, for example, that exercise can alter the form of the body. Bodybuilders have a certain look, sprinters look differently than marathon runners, swimmers have differently shaped bodies than gymnasts. So, the question isn’t whether exercise can alter your body. The question is how does exercise alter parts of your body that are injured and specifically cartilage.

Most everyone agrees that injured bone heals best with the application of force; controlled of course. If you break your lower leg, for example, optimal healing always includes graduated weight-bearing. If you place too much load on the fracture too quickly, you’ll impair the healing. If you don’t place enough load on the fracture, you’ll also impair the healing.

I invented nothing new here in terms of how the body heals. The science supporting the idea that cartilage has healing capability is extensive and beyond the scope of a single blog post but basically it heals in a similar way that bone heals (which makes complete sense when you consider that cartilage is the predecessor of bone) – controlled compression and decompression of the joint via controlled loading or weight-bearing.

Joint cartilage is “mechanosensitive” – it responds to motion and load to both maintain its health and improve it. The cells responsible for helping injured cartilage heal only “speak” to each other once force is applied. This is in contrast to, for example, the skin where blood is plentiful and cellular communication almost instant. The key for cartilage to heal, once injured, is finding the proper amount of motion and load.

…..human cartilage responds to physiologic loading in a way similar to that exhibited by muscle and bone, and that previously established positive symptomatic effects of exercise in patients with OA may occur in parallel or even be caused by improved cartilage properties.”

But, the wild card is how well does it heal; what’s the quality of the tissue? In some cases, the damaged cartilage will repair itself with tissue that is not the same; closer to a scar like tissue. In other cases, the cartilage may heal with higher quality tissue. In any event, some healing is better than not having it happen at all.

Turns out, some researchers from Australia studied the knees of 86 healthy subjects and initially found 19 cartilage defects where roughly one-half of the cartilage had been lost. Two years later, the subjects had MRIs to inspect the joints. Of those 19 locations, more than half improved, less than a third worsened, and the rest remained the same.[source]

Even more incredible was that in five areas where bone had been exposed (where the cartilage had been lost) four of the five showed evidence of new cartilage during the re-examination and one was at full thickness.

Evidence

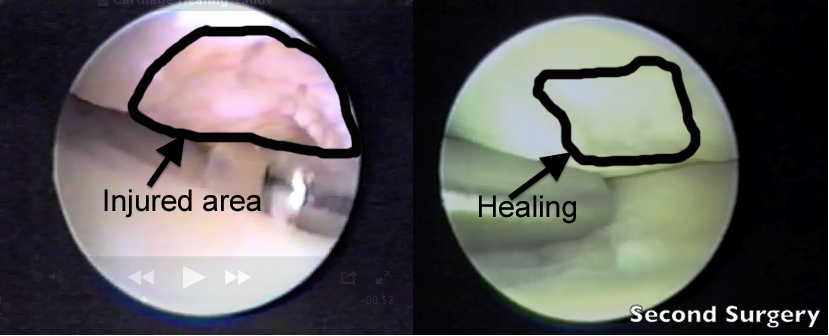

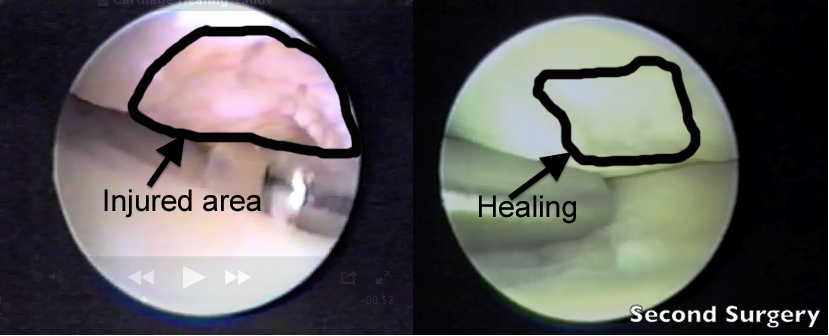

The images below are from a case study. A woman in her 40’s came to see me with a diagnosis of “knee pain”. She first saw her family doctor who prescribed an anti-inflammatory and to stop her bench step aerobics classes. She followed his instructions, went back to see him after four weeks and was told she could resume her regular routine.

So, she goes back to step aerobics and about two weeks later, her knee swells to the size of grapefruit. She then goes to see an orthopedist who sends her to me after having performed a knee arthroscopy.

We guided her through our cartilage conditioning/strengthening program. About three months later, she had no swelling, could bear above bodyweight force on her leg and felt great.

About a year later, she returned to my office with a new diagnosis. She had taken a hiking trip in the mountains in Mexico, got her leg caught between some rocks, twisted it and tore her meniscus in the same knee.

The image on the left is from her first surgery. The arrow is pointing to a large defect in her femoral condyle. In technical terms, that size of defect is called a “mid-thickness” injury and is thought to never heal. The image on the right is the same knee about a year later during surgery for the meniscus tear. The arrow is pointing to the original area of the defect that now has filled in about 90%.

And below is a video of the first and second surgery. Pay special attention to the change in the firmness of the cartilage in the second video.

Why Strengthening Muscle Is So Difficult With An Injured Joint

For those of you reading this who have had, or currently have, knee pain from a joint cartilage problem, you will probably recognize the following scenario.

Because the vast majority of providers still believe there is no hope for injured cartilage, all that is left to fix is either mechanics (how you move, how flexible you are, how well “aligned” your body parts are) or muscle strength.

And here’s what happens, most of the time, when you perform strengthening exercises in the presence of a joint cartilage problem as presented to me by one of my students several years ago.

“So, how’s it going with Mr. Smith?” I asked.

“Well, okay I guess,” replied the student.

“Okay? What are you doing with him?” I asked.

“Oh, quad strengthening of course. Mostly trying to get his VMO to work, ” she replied (VMO is the vastus medialis oblique – one of the quadriceps muscles).

“I see. And how many reps are you using?”

“3 sets of 10 reps,” she replied with confidence.

“Okay and how much fatigue would you say Mr. Smith has in his muscles from the 3 sets of 10 reps?” I asked.

“Uh…what do you mean?” she replied.

“I mean, how tired does his leg get from the exercise,” I replied.

“Oh, well, I don’t know really. I guess, well, I guess I didn’t ask,” she replied.

“Go check it out and come back and let me know what happens,” I said.

Off goes the student to work with Mr. Smith. A few minutes later, she returns.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Well, he didn’t have any fatigue really at 3 sets of 10,” she replied.

“And what did you do?” I asked.

“I increased the weight but then he couldn’t do more than about 3 or 4 reps and his knee hurt,” she replied.

“So what did you do then?” I asked.

“I lowered the weight and asked him to go until he fatigued. And he did about 50 reps and still wasn’t all that tired so I stopped,” she said.

“Right. Okay, so now what?” I asked.

“I have no idea really. I was hoping you could help me,” she replied.

And that’s how it goes. A lot of people wasting a lot of time trying to strengthen muscles that cannot be strengthened because the effort overloads the joint.

Sound familiar at all?

What To Do

I go into considerable detail about the strategy and tactics for knee joint cartilage in my book “The 90 Day Knee Arthritis Remedy”. Covering the entire book in a single post is not possible but here are some of the basics.

Determine how much force your joint can comfortably withstand and respect it. I have worked with clients who could tolerate 30% of their body weight on their injured leg yet refused to stop running. For example, someone who weighs 150 lbs, may be able to withstand only 45 lbs of their body weight on the painful leg while the other leg can withstand more than 150 lbs. Running produces forces well over bodyweight loads.

Injured tissue heals faster when you give it what it needs. Otherwise, it will just fight you the whole time until eventually you’re forced to stop the activity and then are faced with a much more difficult problem to solve. I like to use the Variable Incline Plane (VIP and I have no affiliation with any companies) because I can find the threshold at which you can comfortably load your leg. This information is invaluable as a training metric and for comparison over time.

Move your joint lightly, easily, and intermittently. Injured joints like movement, generally, and dislike being still. For an injured knee, I suggest things like a furniture slider, or even a paper plate to place your foot on and slide the foot forward back while in a sitting position. You can do this for 5-10 minutes a few times a day and most people find it quite helpful.

Find a repetitive motion you can do without pain and do it thirty minutes a day. I like a VIP because it’s easy to find a comfortable load level to perform squats. Other options include cycling, walking in a pool, some elliptical machines. Remember that you have to gradually increase the load or pressure in order to strengthen the joint surface. The biggest mistake people make is keeping the load levels the same for long periods of time or increasing the loads too quickly.

Eventually, you must strengthen your leg muscles – all of them. But to get to that point, you have to address the weakness of the cartilage.

Leg strength is built from the inside-out.

In the meantime, the old standby that almost everyone uses, quad sets, is a good thing to add but not because it helps strengthen your quadriceps (which it doesn’t). You’ll get more out of the exercise if you tighten the quadriceps muscle with your knee nearly straight while, at the same time, you tighten the hamstrings. The “setting” of the muscles increases the thickness of the synovial fluid which in turn helps improve the nutrient exchange within the joint and serves as an extra “cushion” when you place weight on your leg.

Add supplements. I suggest Chondroitin Sulfate and Glucosamine. I recommend Osteo Bi-Flex or Triple Flex brands (these supplements are not regulated by the FDA so quality control is a common issue and these brands have been tested and found to contain what they advertise). I also suggest Boswellia which has been shown to help reduce joint-related aches and pains.

Consider Platelet Rich Plasma Injections (PRP). I had a large medial meniscus tear in my right knee a few years ago. Having been through surgery for a tear in the other knee back in 1994, I didn’t want to go through surgery again. Preserving as much of the meniscus as you can greatly helps long term knee health. I chose to undergo a PRP injection (twice) in the right knee. I also followed strict weight-bearing restrictions following the injection and adhered to my rehab program. It worked. My meniscus healed and today the only thing about my right knee that isn’t “normal” is I have a very slight loss of passive knee flexion. But otherwise, it feels great and my function is very good.

Expect setbacks. Cartilage is finicky. Too much pressure, too fast and a few days later your joint will ache or swell or hurt. Not enough pressure or if the progression is too slow, and you’ll not improve much. The result is a cyclical process of improvement, then maybe a setback or two, then some improvement and then perhaps no improvement. If you have a load level test from a device like the VIP, this helps you manage the setbacks. You might think you’re worse than you really are. Numbers help.

Be patient. Healing an injured or weak joint takes time. Sometimes, a long time. Like several months or even two or three years. You have to keep working at it; keep showing up. It’s simple but not easy to do.

Maintain your improvements. Once you’ve re-established your load capacity, you have to train or exercise consistently with joint-friendly exercises to keep it there. It’s a lifestyle; a commitment. If you don’t do this, you’ll gradually decline and eventually, the problem will come back. Your body makes you earn your health.

Thanks for reading.