- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- Joint Health / Pain »

- Quick Fix for Knee Pain?

Quick Fix for Knee Pain?

The urge to get better quickly is normal, common. Pain is unpleasant even though it’s just a sensation like an itch is a sensation.

At one time, scientists placed itch and pain in the same category with itch being a lower level of pain.

Turns out that itching has its own neural configuration separate from pain but the itch is still unpleasant especially if you can’t scratch it.

And maybe that’s why it’s not all that unpleasant unless the body part is in a cast. Itching has a quick fix and most of the time, a long-lasting one.

Pain is trickier than an itch. Two-thirds of the pain experience is not physical. Mental, emotional and physical inputs make up the pain experience.

A quick fix is harder to find for pain than like an itch. Sometimes you can extinguish pain rapidly but most of the time, pain is an expression of a problem or an indicator much like the function of a vital sign.

Is there a quick fix for knee pain or, more specifically, kneecap pain?

Search engines, like Google, are a great resource but can also be confusing. When you search for something like “why does my knee hurt?”, you’ll get a gazillion answers.

One of the more popular suggestions is that something is “off” about the kneecap. It’s either not in the right position or it moves incorrectly. The reason it moves wrong, in theory, is from an imbalance between the muscles on one side of the kneecap versus the other. Either one muscle is too tight or another muscle is too weak.

So, the fix is to correct the bad position or movement. You do this by either stretching one part of the thigh muscles – the outer part of the quadriceps muscle – Vastus Lateralis (VL) and the Iliotibial Band (ITB) – , strengthening the inner muscle – the Vastus Medals Oblique(VMO) – or using some type of manual technique to “release” the tight tissue whether that’s the muscle or even a tiny part of a tight muscle referred to as a “trigger point”.

Although the kneecap position theory of why you have kneecap pain is flawed, getting relief is sometimes remarkably easy.

Here’s what’s going on.

First, there’s no science to support the idea that knee pain is caused by a poorly positioned or poorly moving patella (kneecap).

In one study, researchers tested 74 patients diagnosed with patellofemoral pain syndrome (pain in and around the kneecap) and examined the relationship between pain and biomechanical factors – muscle weakness, tightness, anatomical abnormalities, coordination problems, and even posture. They found no correlation with between the biomechanical factors and anterior knee pain.[1]Piva SR, Fitzgerald GK, Irrgang JJ, et al. Associates of physical function and pain in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Feb;90(2):285–95. PubMed … Continue reading

But, nonetheless, sometimes, people improve with something like, for example, stretching the Iliotibial Band or rubbing it. Why does this happen if there’s no relationship between tightness, tracking, weakness, and pain? And if you can’t really stretch the IT Band, why does that seem to help?

I’ll answer that but there’s more to cover first.

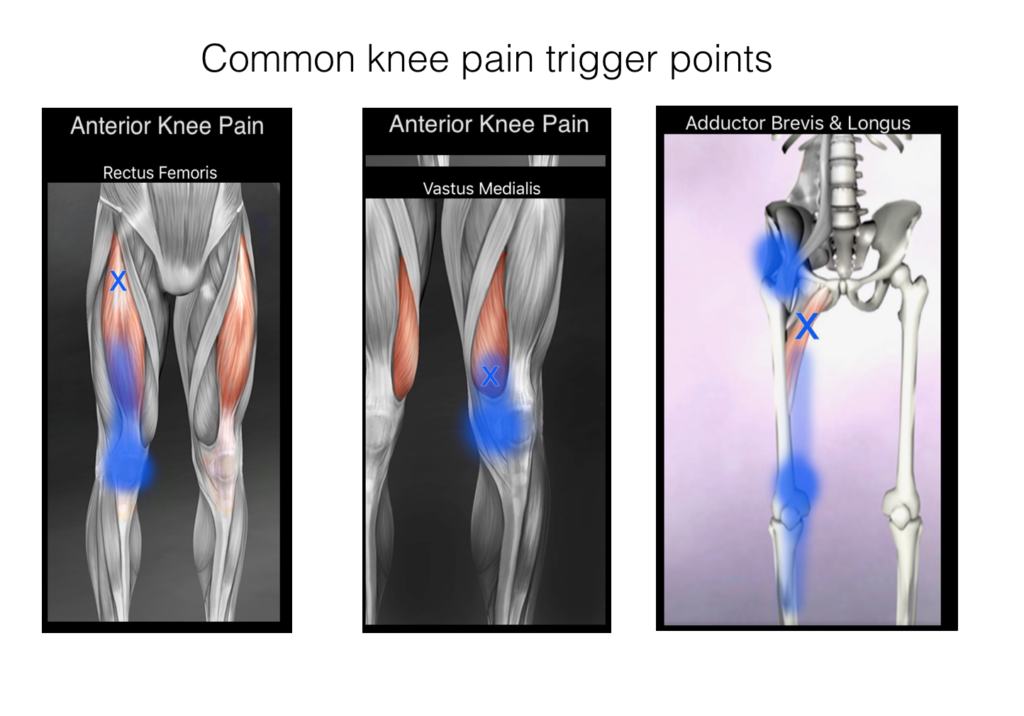

A trigger point is a small, localized area of muscle that is exceptionally tender, tight and painful. “Active” trigger points refer pain to other areas of the body whereas an inactive point hurts only if you press on it. With anterior knee pain, the trigger points will be located in certain spots in the thigh – most often the ones in the image with the “X” (notice that the trigger points for anterior knee pain are only on the front of the thigh).

How trigger points happen is controversial. A likely explanation is that a small area in the muscle cramps in response to some type of overload – kind of a micro-cramp – and, as a result, decreases the flow of blood and oxygen. This causes the pain, tenderness which sets up a nasty feedback loop. Less oxygen -> more cramping. Why just one tiny area? I don’t know and I don’t think anyone else does either.

One way to interrupt the cycle is to apply pressure to the trigger point. You can also needle the point but, for most people, manual pressure is the only option. The results can sometimes be stunning. In a matter of moments, you can go from annoying knee pain to being pain-free.

But…

Most of the time, trigger points are not the main problem but are secondary problems. A weak joint will almost always have associated trigger points either active or inactive or both. And often times, people have joint symptoms but they don’t realize it. Transient aching, stiffness, pain that comes and goes are all signals your joint needs some help and those symptoms might come and go. They’re easy to overlook.

When you dig into the history of a complaint, you’ll usually find these kinds of symptoms along with the trigger points.

By treating the points, you may get pain relief but you leave the underlying problem intact.

Ok, so why does this stuff work then if there’s no correlation between the biomechanical findings and knee pain?

The one thing that is common among all types of manual therapy and even some forms of exercise & stretching, is the activation of pain-inhibiting mechanoreceptors in the skin and soft tissue of the area being treated and any associated pain referral areas.

A mechanoreceptor is a specialized sense organ or cell that responds to pressure, tension, vibration, temperature. These cells send messages to the brain by way of the spinal cord and can inhibit the pain signal. In a way, they’re like a dimmer switch on a light. Mechanoreceptors can decrease the perception of pain or, sometimes, eliminate it just like dimming a light or turning it off.

Anytime you mechanically stimulate the body – massage, trigger point treatments, active release, myofascial release, foam rolling, tennis balls, stretching, taping, neoprene supports, various movements, etc. – you are activating mechanoreceptors. This is why you feel better and not because you’ve changed anything with how the kneecap is positioned or moves.

In addition to the physical effects, mechanical stimulation also carries with it emotional and even mental effects. Touch used by a skilled clinician can be a powerful anti-pain tactic that impacts the other two-thirds of pain – but that’s for another day.

I’m not suggesting you should avoid “quick fixes” for knee pain. My goal is to help you understand how the system works so you have the best outcome. All of the various methods I mentioned have a role in overcoming knee pain and can help reduce knee pain. But, most of the time, even if it seems like a quick fix, it’s a temporary quick fix.

Thanks for reading.

PS – If you like this article, why not share it with a friend?

References

| ↑1 | Piva SR, Fitzgerald GK, Irrgang JJ, et al. Associates of physical function and pain in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Feb;90(2):285–95. PubMed #19236982. |

|---|