- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- Joint Health / Pain »

- What’s the Story on Knee Cartilage Injuries?

What’s the Story on Knee Cartilage Injuries?

From a reader recently:

Hi Doug, do you have any recommendations for doctors and/or physical therapists in the New York City area who follow your way of thinking about cartilage regrowth? I am frustrated by the focus on my quad muscles and general pessimism. Please let me know of anyone who comes to mind! I would be so grateful.

-AW

I need to explain my thinking on “cartilage regrowth” as it pertains to weight bearing joints like the knee.

I’m a “word” guy.

I’m perhaps a bit persnickety about words. Ask my wife, Elle. She’ll confirm that for you. I am, sometimes, a pain in the butt to live with because I will answer her question with a dissection of the word followed by a new word.

“So, are you excited about where we’re going this weekend?” she’ll ask.

“Excited? Hmmm, no, I wouldn’t use the word excited. I would say I am more curious than excited,” I’ll reply in my unintended imitation of Mr.Spock from Star Trek…raised eye brow too.

See how great it is to live with me? In fact, when Elle came to my classes to observe and help, students asked her what it was like to live with me. She said, “Oh, he’s just like this at home.”

But, in my defense, words matter. If I tell you, after a consultation for a knee injury, that “you’ll be fine”, in your mind that might mean you can run marathons again right after the rehab finishes while in my mind it might mean you’ll have normal motion, no pain and enough strength to perform everyday tasks.

I’ll bet, when you were in college and missed a question on an exam and, as a result, you got a B instead of an A, you argued with the professor over how some of the questions were worded.

Right?

Some of my students confused the word “repair” with “regenerate” and used them interchangeably.

They mean different things.

Repair versus regeneration.

Repair means the wound can heal but not with the same tissue or quality as before the injury. Regeneration means the wound heals with the same tissue and quality as before the injury.

Bone regenerates.1 Muscle leaves a scar. Cartilage leaves a scar.

Now, that last statement about Cartilage was considered controversial in the late 80’s and early 90’s. It’s still controversial with some practitioners.

The thinking back then was that a Cartilage injury did not heal and would continue to degrade over time. I was taught that too in PT school.

The main reason people believed that Cartilage could not heal was that Cartilage has no blood supply and therefore has no metabolism.

No blood, no metabolism, no healing. End of story.

I’ve always had an issue with this line of thinking. When I was in PT school, I asked one of my professors how that was possible.

“What do you mean?” he replied.

“I mean why is a tissue with no metabolism in the body? How does it get there, develop? That doesn’t make any sense,” I explained.

“Well, cartilage is an exception. The fluid in the knee keeps it alive,” he said.

“But, didn’t you say that cartilage has no metabolism?

“That’s correct. It does not,” he replied.

“That means it’s not alive, a non-living thing, inert, like a chair. How can something be kept alive if it has no metabolism? If it’s biologically inert, then how did it get there? How does the body create something that is not living, inert? Does your body give it life only to later take it away? And what’s there to keep alive if it’s inert?” I asked.

My questions flew out of my mouth as if the words were knives landing all around his body pinning him to a wall.

The conversation ended with the professor explaining to me that cartilage has no metabolism and cannot heal and that was it.

I missed those questions on the test and argued vehemently.

I lost the argument. Got a B on the test.

Articular cartilage responds to physical stress in the same way that muscle and bone do. It’s science.2

With the proper load and motion, cartilage responds and adapts to the physical stress by increasing its’ strength or structural integrity. Notice I didn’t say that it regenerates because it doesn’t. But it can increase it’s inherent strength.

According to one of the authors of the study,

“This study shows compositional changes in adult joint cartilage as a result of increased exercise, which confirms the observations made in prior animal studies but has not been previously shown in humans,” notes Dr. Dahlberg. “The changes imply that human cartilage responds to physiologic loading in a way similar to that exhibited by muscle and bone, and that previously established positive symptomatic effects of exercise in patients with OA may occur in parallel or even be caused by improved cartilage properties.”

The only way that cartilage could respond to physical stress is if it does have a metabolism. Healing or repair requires energy. The problem with cartilage though is that the metabolism is sluggish. My professor was correct that the synovial fluid is part of the nutrient source for repair and the other is the blood underneath the bone which diffuses into the joint.

Because the metabolism is slow, cartilage needs dedicated movement with the proper load but more repetitions, more movement than a tissue like muscle. And the movement must not cause pain or other symptoms. If you ignore this and don’t provide the needed stimulus then, yes, the injury worsens over time.

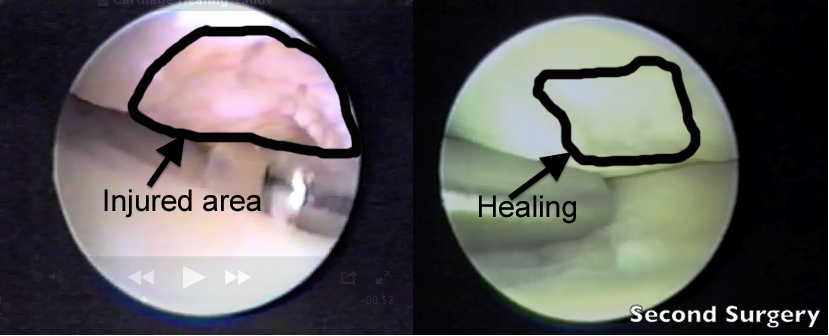

The image below is from the knee of one my former clients who had an articular surface injury (cartilage injury) of her right knee (the injury is on the left side of the photo – taken during the first surgery). The circled area is the end of the femur or thigh bone and you can see there is a decent sized divot. A chink of the cartilage is gone. The surface should be smooth.

The image on the right side is three months later of the same area in the right knee. The divot has filled in. That’s a scar but functionally for the client, she felt great.

What you can’t see is the change in the firmness of the tissue. In surgery #1, the tissue is soft, mushy and easily deforms to the pressure of a probe. In surgery #2, the surface is firm and slippery.

Her surgeon called me. He said it was the first time he had ever seen this kind of healing in a joint surface injury and that usually, the injury gets worse. “So, all that stuff about cartilage strengthening that you’ve been talking about, you were right!” he said in an excited voice.

I think the word “regrowth” is used with regeneration in mind. But, you know now that cartilage does not regenerate. It can heal, form a scar, strengthen and that’s a better result than not healing, or worse, continuing to degrade.

A deep enough wound of the skin, needs to close, heal. It forms a scar. Having a scar serves to protect the body and that’s also true for cartilage. But, there are situations though where there has been too much damage to the tissue. I’ve had clients come to me hoping they can avoid surgery but their joint surface was too damaged. In those situations, people usually end up in surgery with either a partial or total knee replacement.

If it were me though, I would seek out stem cell therapy before I would consider surgery. The stem cell arena is just exploding with great promise. But, it’s a bit of the Wild, Wild West right now and is considered experimental. But I’m an experimental guy. I used PRP for a meniscus tear in my right knee that. at the time, was not used for the size of tear I had. Surgery was the common procedure. But I wanted to see what would happen and also to figure out the post-injection process. I had a great outcome.

I digress…more on that stuff later.

If any of you reading this have taken course work from me and would like to be on my recommended practitioner list, please hit REPLY and send your name, office address, telephone number and your email address.

That’s all I have for now.

Thanks for reading.

PS – If you’re interested in what I do for exercise and training, go here. For my books, go here

PPS – If you like this article, why not share it with a friend?

- Marsell, R., & Einhorn, T. A. (2011). The biology of fracture healing. Injury, 42(6), 551-555. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031

- Roos, E. M., & Dahlberg, L. (2005). Positive effects of moderate exercise on glycosaminoglycan content in knee cartilage: a four-month, randomized, controlled trial in patients at risk of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum, 52(11), 3507-3514.